The Making Of A Poet Laureate

By Sarah Elkins

It’s hard to know when a poet first becomes a poet. For Marc Harshman, maybe it was in childhood when his father would recite James Whitcomb Riley. Or perhaps it was when he wrote his own Riley-inspired piece in the second grade and his teacher castigated his use of dialect. Indeed, there is a little masochism in all writers. But, if you ask him directly, he’ll joke that in high school he first aspired to be an athlete but failed. Then a rock ‘n’ roll star, but no.

“To win the girls, mind you,” he’ll say, pausing to look at you over the top of his glasses. He’s told this story before, and it’s a good enough answer to an impossible question.

“I thought, well, I’ll try poetry,” he’ll say. “That didn’t work either, but I’m still doing it.” If there’s an audience, people will laugh. This is a half-answer, not a lie but not the whole story.

Marc was raised on a farm in Indiana, and by the time he was a teenager−sports and music aside−he was “dying to be a full-fledged hippie.” A member of the Disciples of Christ, a liberal protestant denomination, and involved in state-level church leadership, he was traveling frequently to cities like Indianapolis where he tapped into the beatnik movement sweeping the country.

The summer before his senior year in 1968 he was invited to attend the White House Conference on Children and Youth. As providence would have it, his roommate for the week-long conference was the leader of Princeton’s Students for a Democratic Society.

“I was already getting radicalized by this point,” he recalls.

Throughout the week, the students worked to draft a plank that would be presented to the Nixon administration as the official statement from the youth of America. “It was very anti-war, very civil rights, and they wouldn’t let us do it. They had another plank that was all milk toast,” Marc says.

So, the students availed themselves of a xerox machine somewhere in the city and made copies of their plank. They stood outside the Capitol handing their uncensored platform to everyone who entered, including the press. Marc was younger than his cohorts, still a clean-cut high school kid. In the photo that would be published in the Washington Post later, there were “guys with afros, and guys with long hair, and girls with their peasant blouses, and me in my coat and tie,” he laughs.

Around the same time, Marc was discovering the beat poets whose work was being published in the underground magazines that would arrive in his mailbox. How his parents allowed them in the house he doesn’t know, but he was mapping the course for a life steeped in language.

“When I read Howl by Ginsberg for the first time, it really ignited something in me,” he says. Perhaps that was the moment the poet was born. He admits, “The poetry I wrote for the next many years was really terrible because it was with no discipline, but I was doing it. It was pouring out of me.”

In 1969, Marc would attend Bethany College in the northern panhandle of West Virginia, the flagship university of the Disciples of Christ denomination, on scholarship. In short order he flunked most of his classes and lost all his scholarships.

“I made lots of terrible, even potentially dangerous mistakes. It really was drugs, sex and rock and roll for years. I look back and see many friends who didn’t make it in one way or another,” he says.

Luckily, Bethany was small enough that when Marc fell there were people to catch him. He fears he would have fallen through the cracks at a larger school, but with good mentors he clawed his way back into good standing. After a devastating first year he would graduate cum laude in religion, English and theatre.

While at Bethany, Marc studied with excellent professors hailing from Yale, Harvard, Oxford, and Columbia. He recalls, also, when Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Galway Kinnell visited the campus.

“I still can’t believe it happened,” he says. “I had a half an hour or more alone with him, just one-on-one and he’s reading my poems and we’re talking. It’s embarrassing to think back because I know what my poems were like at that point.”

In the college’s literary magazine, he says, “I have the immortal line ‘fucking great yellow daffodils.’ This is the kind of drivel I was writing.”

Someone saw the glimmer of promise in Marc. Larry Grimes, the professor who taught him how to read Joyce’s Ulysses (a thing a person doesn’t just pick up one Saturday) and who introduced him to Joseph Campbell’s myth of the hero wrote his ticket to Yale Divinity School where he would go next.

Yale represented for Marc a cultural awakening and journey to real adulthood. Here he would be immersed in the music, art, and political discourse happening at the forefront of the post-civil rights era. He would work in the inner city, something he says was frightening and revelatory at the same time. On weekends he visited friends at Columbia in New York City.

At the same time, Marc’s parents are divorcing and his wife-to-be Cheryl, whom he’d met at Bethany, is studying overseas at Oxford University. They write to each other intensely over a year that is personally and socially revolutionary for him.

“I don’t think I’ve ever said this aloud to anybody, including Cheryl, but I wonder now if that didn’t really cement our relationship,” he says. “I’ve become a big believer that correspondence can provide an intimacy unlike anything I know in this world.”

In his second year at Yale, Cheryl, now a Bethany graduate, joins Marc in New Haven. And, his brother Craig, three and a half years his junior, is diagnosed with testicular cancer. He flies to and from Indiana frequently that year to be with his brother, foregoing his graduation from Yale to be at Craig’s bedside.

In the wake of his brother’s death that June, Marc and Cheryl decide to stay on in New Haven for another year. “I’m completely strung out at this point, no idea what my future holds, but I realized I didn’t want to teach at the college level,” he says.

Marc is mulling the idea of pursuing an MFA in creative writing in the fledgling program at the University of Pittsburgh when he and Cheryl take a Valentine’s-weekend trip to Manhattan to attend a party for the Jargon Society. The Jargon Society was a publisher printing the post-beat poetry of the Black Mountain poets whom Marc is devouring. The event is at the Gotham Book Mart in Manhattan, the vanguard of literary book shops on the east coast, haunt of Rudolph Valentino, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, and Andy Warhol.

“We walk into the party at the Gotham,” he remembers, “and, there are all my heroes right there in the room. There’s Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti and many others.”

Marc and Cheryl find a spot in the corner and watch. At the end of the evening, they take a bibliography of all the titles published by the Jargon Society and where they can be found: two stores in London, the Gotham there in NY, City Lights in San Francisco, and then an asterisk−

“And still the best place to find all out-of-print titles is the Asphodel Bookshop, Ravenna Road, Burton, OH.”

This is funny to them because Burton, Ohio is a sleepy little farm town near Cheryl’s hometown west of Cleveland, an unlikely bastion of American arts and letters. The following summer, though, Marc and Cheryl are to be married in her parents’ backyard before moving to Pittsburgh where Marc will begin school. On one of the several trips between New Haven and Cleveland in the preceding months, they stop at Asphodel Bookshop and meet owner Jim Lowell. The bookshop is a converted garage identifiable by a pink mailbox that says Tessa’s Beauty Salon. Tessa, Jim’s wife, is a British expat who emigrated after the war. Together they were the unlikeliest couple in the unlikeliest nook of the country.

“There were all the magazines I had heard about from all around the world. There were first editions of Hemingway and Faulkner and Joyce. There was original sheet music by Debussy and Erik Satie and Charles Ives. Broadsides and posters on the walls. There’s a picture of Allan Ginsberg standing with Jim,” Marc lists his memories of the place he would continue to visit until Jim’s death in 2004.

“He shaped my taste. He taught me more just by example, by what to read, than any professor I’d ever had. He remains the single greatest influence in my literary life,” Marc says.

The next years at Pitt result in an MA in English Writing, an invented degree so that Marc could graduate because the MFA licensure had not yet been finalized.

“As it turns out, it didn’t make any difference,” he admits.

Cheryl would land a good fulltime position as a librarian in Moundsville, WV, and, after a couple miserable years as part-time faculty at West Virginia Northern Community College, Marc begins teaching 5th and 6th grade, something he will do for the next dozen or so years. In 1983, he publishes his first chapbook of poetry, Turning Out the Stones, by State Street Press.

In January of 1989, Marc & Cheryl’s daughter Sarah is born, and his first children’s book, A Little Excitement, is published. The book gets rave reviews and “I saw real money for the first time in my life,” he says.

“I thought, I should keep at this, and I did. I’ve now just published my 14th children’s book.”

Since those early years, the publication of children’s books has continued to fund what Marc calls his “poetry habit.” He publishes 4 more chapbook collections before his first full length, Green-Silver and Silent, comes out in 2012, the same year he is named the 7th poet laureate of West Virginia.

His predecessor Irene McKinney had passed away in February when in May Marc finds himself, as he often is, “in a little grade school somewhere, being a children’s author.” His cell phone rings in the midst of his presentation. The phone is his daughter’s cast-off flip phone and the ringtone is the Indiana Jones theme song. He’s embarrassed at his failure to turn off his phone when he flips open the phone and slams it shut, hanging up on whoever had called. On his drive home from the school visit, he calls the number back to discover Governor Earl Ray Tomblin has appointed him the state’s next poet laureate.

He asks, “Are you sure you have the right person?”

“This is terrible,” he laughs now. “I said, ‘Can I call you back next week?’”

Soon home, he tells Cheryl what happened, and she yells, “You said what?!” Incidentally, he calls back to accept the appointment that day.

Prior to becoming the laureate, Marc was perhaps more widely known for children’s literature. But, he says, “I have always been a poet first, before anything else. It’s what I have to do. It really is what I’m called to do. At least at this point, I can’t imagine not writing, whether I’m publishing a word.”

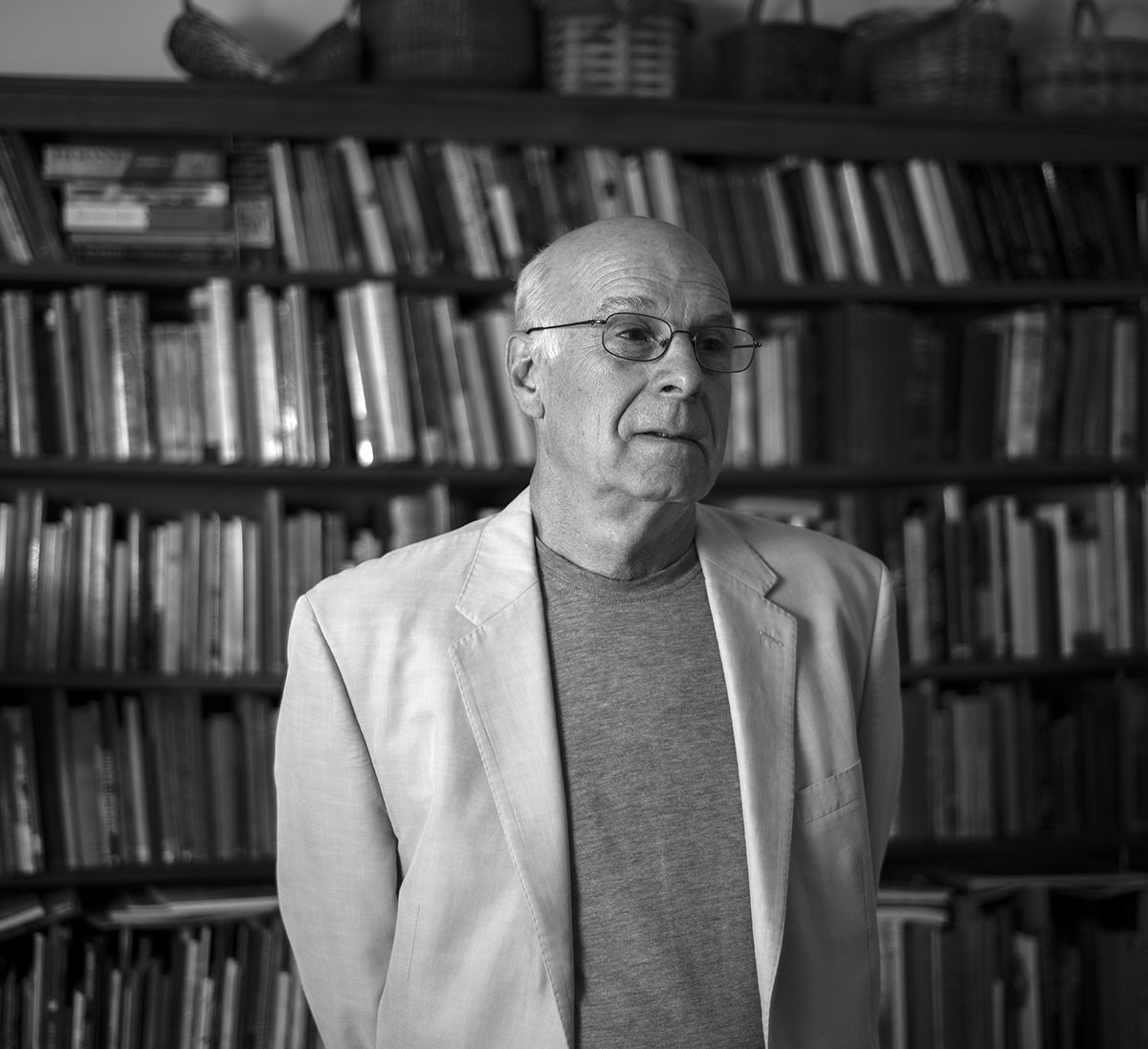

Now in his eighth year as poet laureate and decades since his hippie renaissance, the long hair and beard are gone, but he still carries the lankiness of youth. He has an easy way of leaning into the person he’s talking to, a storyteller’s habit, also one of tall people who wish not to loom. Even when standing, there is the muscle memory of having folded himself into elementary school chairs to lean in and tell stories to very little people. This is a good quality in a laureate.

This past November, Marc spent an hour on stage at Lee Street Listening Room in Lewisburg reading from his newest collection Woman in Red Anorak. It had just been released by Lynx House Press, having won the Blue Lynx Prize the year prior. (An anorak is a windbreaker, if you’re wondering.)

He stood on stage in a white button-down shirt, splattered in black paint like a Jackson Pollock canvas, paired with a sport coat for good measure. Instead of opening with one of the poems from the new book, he decided to read a brand-new poem.

“I never do that. I never do that,” he said. And then he did. Two weeks prior he had been in Charleston, WV at Taylor Books to give a reading. So too had Ivanka Trump−been in the Taylor Books in Charleston, that is. She was waiting out a flight delay along with an entourage of Secret Service agents, a surreal moment for everyone present.

“Perhaps she’s come to be converted,” Marc speculates from his poem. Then, more reasonably: “She’s here for fine coffee.”

And, finally the most reasonable response to reading poetry while Ivanka Trump stands aloof in a back room dressed in all white: “What the fuck…”

These days Marc mostly passes for the polite intellectual type−paint-splattered shirt notwithstanding−the sort invited to important events to deliver keynotes, the sort to receive honorary doctorates. But, as is the case with the long-radicalized, he’s not wearing anything on his sleeve. He requires a close read.

Right now, all the extra leaves have been added to his dining room table where he’s sorting through two, maybe three, manuscripts. He’s trying to work quickly because Cheryl can’t have any company until some order is made from the thousands of pages. He’s doing the best writing of his life now, he thinks.

“Sometimes I hate it all. But, in the end I probably like it more than I should. It’s a whole minefield of question marks about who in the hell would want this. There are never any guarantees,” he says.

And, from the poet who has been pouring out words for sixty-odd years: “I’m still here. I’m still doing what I want to do. All the regrets seem not worth an ounce of piss.”