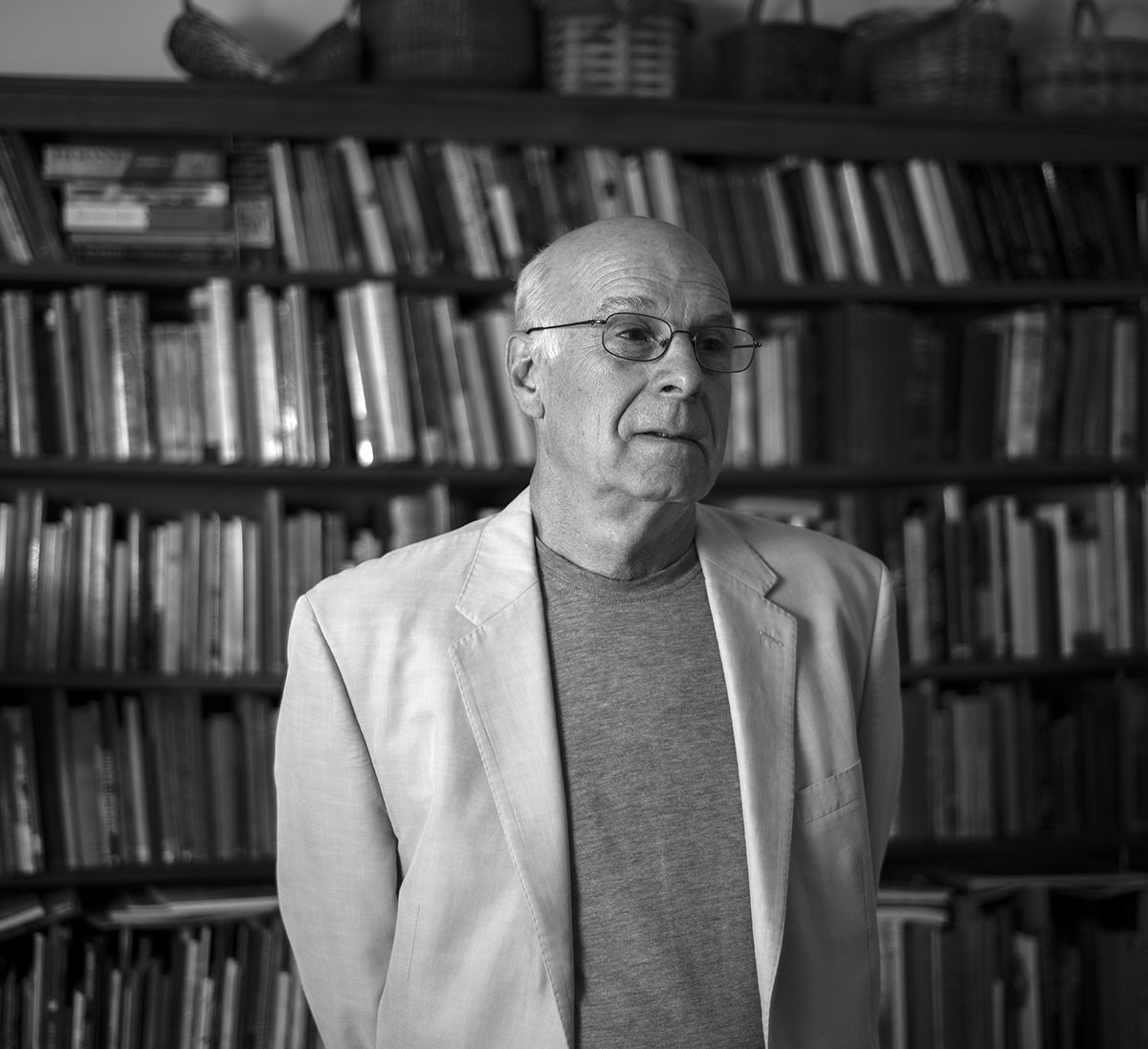

Lynn Boggess

Fourteen years ago we had the pleasure of featuring plein air artist Lynn Boggess. His work had just begun to gain popularity not only throughout the Greenbrier Valley, where it majestically hung in the street-facing windows of Cooper Gallery, but across the country as well. Today, Boggess’s paintings hang in galleries in Sante Fe, Jackson Hole, Asheville, Alexandria and beyond. Those that purchased his work in the early 2000s have seen their values quadruple and his star ascend quickly. He now has over 35,000 Instagram followers, where he frequently posts his new pieces.

We recently followed Boggess out to a small clearing on his 100-plus acre tract of land in Nicholas County as he set up to paint one of his mesmerizing winter scenes. The following excerpts are from our conversations over those two days. Here is Lynn Boggess in his own words.

Photo by Mark E. Trent

The guiding principal I begin with in my work is that art engages life. The more life that is in a painting, the better it has a chance of being. The chaos of life, and also the order of life. So how does art embrace all of that? It’s a complex thing to take on. But it’s an ideal I try to tackle.

Painting is a combination of what we know, what we see, and what we feel. And getting all of that into a painting, and in some sort of equilibrium, is what the style of realism is all about. And that’s why I’m drawn to that style, it’s such a challenge to get all three of those things in flux into some sort of order. It requires a certain intensity to achieve that.

Wilderness in particular is something I am interested in. And I think, like a lot of people, I spend a lot of time indoors. And it’s not so much an unusual thing. We have comfortable homes and we have friends and family there, so that’s a place where we spend a lot of time. Yet there’s another place. It’s a place removed so far from civilization where there’s just rawness—the terrible beauty of wilderness. There’s been many people who’ve talked about that over the years. Ralph Waldo Emerson, of course, has written about it extensively. And John Muir, Rachel Carson, Henry David Thoreau—they have all inspired us to value the presence of nature, in particular wilderness. It’s a place that acts as a kind of counterpoint to modern life. It’s vast, it’s open. It draws us out of ourselves.

And that’s extremely important in our lives now as we live these interior lives, inside of rooms and walls, where our presence takes on more importance than it should. We become monumental indoors. We’re large, we’re controlling. We seem to have all power. But you go out into nature, nature is completely indifferent to us. It puts us in our proper place. It humbles us. And the power of nature, the forces that are acting out there, are completely on their own accord.

We are simply a visitor there. An insignificant part of it, if you will. So nature has a side of life, if we’re talking again about the fullness of life and a complete life. There’s that dimension that is extremely important for people to tap into, I think. Especially in the digital age of the screen, and image, and just the rapid-fire exposure to media that we have.

Henry David Thoreau said it was a wasted day for him if he spent any less than four to six hours out of doors. I often thought when I was younger that that was pretty extreme. But now I understand what he means. I know that if I go more than three or four days without being out and into a session, out of doors into wilderness, I know that that bothers me. It tends to build up a certain amount of pressure that I find is a release when I go out into nature.

Painting is an active sort of meditation for me. And the reason I paint out of doors is it allows me to experience nature first-hand, directly and more intensely than it would be say for instance, having a photo or something on a screen to paint from. Landscape is painting a philosophy. And the more one paints from nature, the more one understands that as being something important to do.

Landscape has a tremendous history to it. It’s one of the most popular subjects for any artist, especially those who are just beginning to paint. It often makes you wonder why a mature artist sometimes invests all time and energy to it. It’s been done so many times. For myself, I would not be painting landscape if I didn’t feel like I was adding something new or different to it.

In that regard, you’ll notice that my paintings are of a vertical nature, vertical format. And the importance of that is that it has a direct correlation to a human being. We are vertical. So, there’s already that connection. The next idea is putting the person there in the scene, and the foreground becomes paramount to that idea. The paint becomes really thick in the foreground. Half of the painting is foreground, which is very unusual for most landscape painters. That’s why I do the vertical formats—to put the viewer right there where I was. And I get comments about that continually that, “I feel like I’m there.”

I’d gravitate towards work that had thick texture. And through a lot of reflection on that, I started to understand what the pull was there. And that was about the tactile qualities of it. Something smooth is often something very removed from us. Something that has a pronounced texture to it automatically becomes part of our immediate surroundings, because we understand space that way.

So what happens when I choose a location? That starts even before I go out. I reflect on how I’m feeling that day and what kind of a mood am I in. From experience of being out of doors, I start to find something compatible in the terrain that will reflect all of that. If I match up my mood with the scene, the painting has a real good chance of coming out well. So, I reflect on that, and I go out and find something. When I first encounter a scene, just as all human beings, I start off with an emotional response. Then I start to understand it. My painting process reflects that attitude to the point where I think it’s something always exciting for me to work with. I do a lot of paintings—hundreds. And it’s because it just never really gets old for me. I start off with the chaos, with the accidents of life. The randomness of it. The scraping of the paint across the canvas when I began. It’s the darkness, the terribleness of life as I see it. I just scrape in all that haphazard chaos. And then I slowly bring that to order. Bring resolution to it. It’s something of a melodrama if you will.