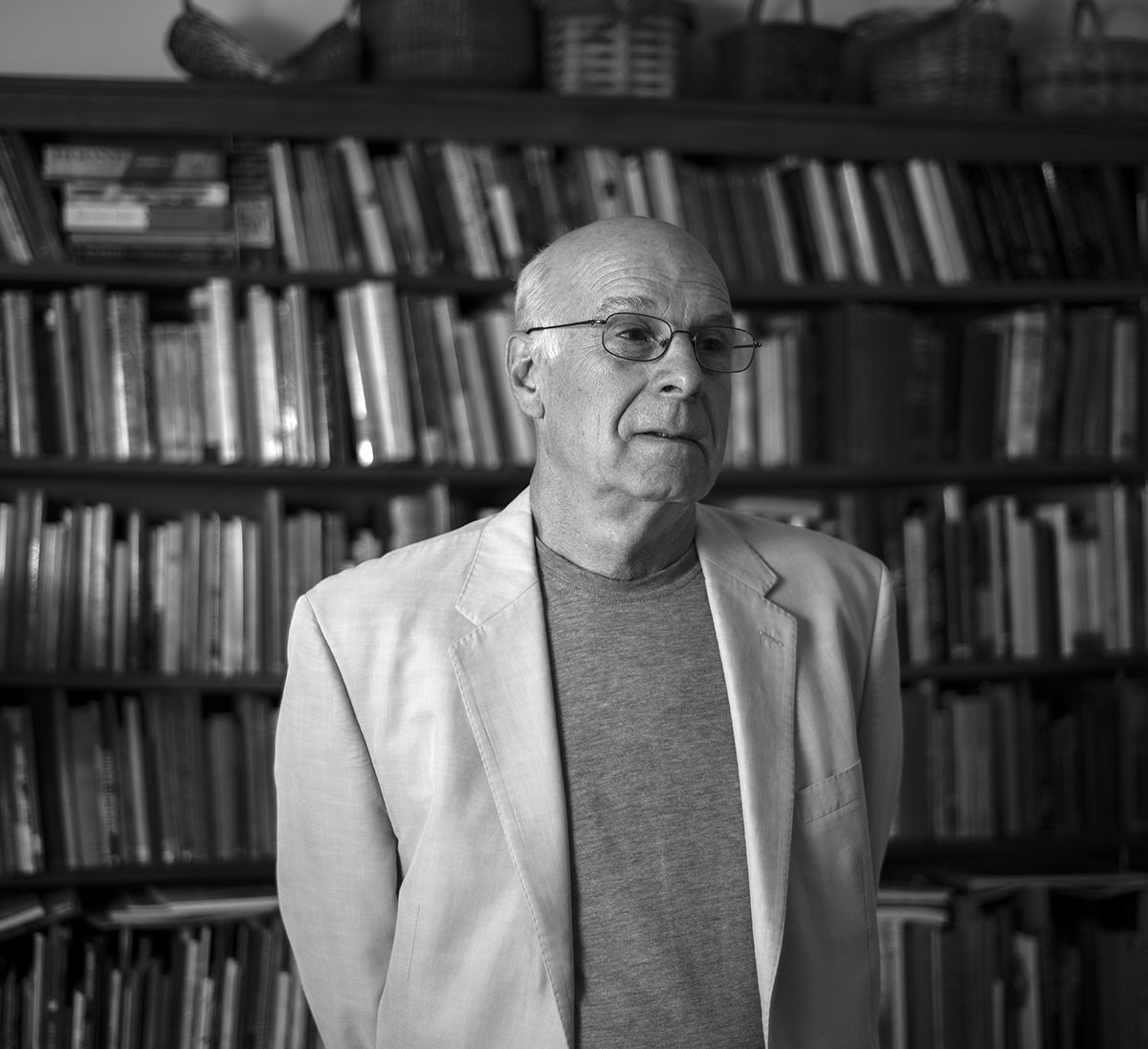

Making Wood Sing – A Visit with Guitar Maker Luke Bair

Story by Greg Johnson

It’s a weekday afternoon and we’re sitting at Luke Bair’s workbench in the middle of his spacious Lee Street workshop in Lewisburg, surrounded by guitar bodies and necks, miscellaneous wood slices, planks and curliques, and even a partially finished six-foot upright bass propped in the corner. “There’s mysticism around the art of building a guitar,” he observes, glancing at pieces of trees that will someday make music.

Luke’s journey into the mystic started with a passing suggestion from his brother as they were hiking on the family farm in Monroe County. He was finishing a hitch in the Coast Guard and he wasn’t quite sure what was next for him. Mechanically inclined, he’d been a carpenter in the Coast Guard and he was learning to play the guitar. “Maybe you should learn to make guitars,” his brother said off-handedly. Something about this captured his imagination. He did a little research and he decided to use his G.I. Bill to attend the Roberto Venn School of Luthiery in Phoenix, Arizona. It proved to be a turning point. “It’s just about the best thing I’ve ever done,” he reminisces.

The 4-month immersive course covered everything from selecting tonewoods to applying decorative rosettes, and he built three custom guitars for himself in the process. The experience was life-changing, one he’s been wanting to replicate for others ever since. This helps to explain why he’s planning to open his own school of luthiery in Lewisburg in 2025. More on that later.

After he graduated from Roberto Venn, he first worked doing repairs at Pickers Supply, a high-end music store in Fredericksburg, Virginia. But after attending luthiery school he yearned to make his own instruments, not repair those made by others. He compares it to building houses. “Building a new house is 100% easier than renovating an old one,” he observes wryly.

He was hired by Huss & Dalton, which was then a new guitar company in Staunton. In addition to Jeff Huss and Mark Dalton, the owners, he was the first employee. It was there he learned production-oriented techniques, which were decidedly different from building custom guitars for individuals. “You strive to create a line of marketable instruments that you can repeat while you continue to maintain high standards.”

Two years later he moved back to Monroe County and partnered with a guitar builder named Scott Mills, who had learned the craft from one of the fathers of American custom luthiery, Augustino Loprinzi. But after his son was born, Luke discovered that while handcrafting instruments was deeply fulfilling, it was a hard way to support a family. Life happened, and for the next 20 years he found himself working as a general contractor building homes while he crafted guitars and mandolins on the side.

Life continued to evolve, and in 2018 he teamed up with Travis Holley to create Appalachian Tonewood, sourcing quality wood for instrument builders around the country, with clients like the Gibson Guitar Company. The forests in our region of West Virginia contain many trees prized by stringed instrument makers, particularly red spruce, which grows at local elevations above 4000 feet. Appalachian Tonewood set up shop at Lee Street Studios, an artist and artisan collective in what was once Lewisburg Elementary School. (Note: If you save copies of the Greenbrier Valley Quarterly, you can read a beautifully written 2021 article about Appalachian Tonewood by Leah Tuckwiller in Issue 64.)

Photo by Mary Baldwin

The availability of workshop space at Lee Street eventually led Luke to return full circle to his first love, guitar building. Travis and Luke now work cooperatively, with Travis sourcing and selling quality tonewoods, Luke building guitars, and local musician Dan Freeman providing instrument repairs, all at the same location.

Operating as the JL Bair Guitar Company, Luke crafts 18-20 guitars a year. Some are commissioned, some are built on spec, and some are for charity. Each year he donates instruments to Healing Appalachia that are raffled off, raising $10,000 - $15,000 for a cause he strongly supports.

He’s often asked if he makes electric guitars. “I’m not drawn to electric stuff,” he says candidly. “I don’t play electric guitar myself. Electric guitars have routing and shaping, but not a lot of carving and steam bending. It’s not the same craft. You can actually buy the body parts and put an electric guitar together yourself.”

JL Bair guitars typically range from $2800-$3500, below typical market price for custom guitars. Guitars from his former employer, Huss & Dalton, run twice that much. Rockbridge Guitars in Charlottesville, which makes guitars for Dave Matthews, are even pricier. And the king of American luthiers, Wayne Henderson, makes modestly priced instruments in his tiny workshop in Rugby, Virginia, that are so coveted they fetch stratospheric prices in the secondary market, explaining why Eric Clapton had to add his name to a long list of prospective customers and wait 10 years to get one.

Meanwhile back on earth, Luke is turning his attention to his passion project, teaching guitar-building. He’s presently working on opening a school for guitar makers. He envisions an immersive course where 5-8 students make two guitars over the course of 10 weeks. As it happens, Lee Street Studios has apartments, which will make it possible for students to come from afar to begin their own journeys into the magical process. “I think it will attract young adults and recent retirees,” he speculates. Somewhat surprisingly, while some guitar makers offer 1-2 week-workshops in their craft, there aren’t any immersive programs in the Mid-Atlantic states similar to the Roberto Venn School of Luthiery. One of Luke’s goals for his school is accreditation, which will make it possible for his students to access financial aid.

Photo by Mary Baldwin

Our conversation turned to his school’s name. “The Lobelia School of Luthiery,” he revealed. “My first child was midwifed by Shay Huffman and we used to go up to Lobelia in Pocahontas County all the time to see her. My wife, Keveney, is a hobby herbalist and her favorite medicinal plant is the lobelia. It’s not that I don’t want to put my name on a school. I just think people relate more to geographic names. Or maybe I’m not very good at shameless self-promotion.”

We took a modest dive into some aspects of his craft that guitar players find endlessly intriguing—types of wood, guitar body styles, how bracing patterns affect tonal quality—topics guaranteed to put non-players to sleep. I came away convinced that there’s no aspect of acoustic guitar making that Luke Bair doesn’t have a thoughtful opinion about.

There’s a danger that sending a guitar player to interview a guy who’s been making them for three decades will tempt the player to commission him to build one, resulting in a very costly interview. Luke’s a great guy who crafts beautiful guitars, but I found myself driving away as quickly as I could, envisioning a red spruce top, mahogany back and sides ...

Finished Guitar - Photo by Jenny Harnish