The Art of Survival

By Barbara Elliott

For more than a century, the distinctive yellow depot was the heart of the community. It represented Marlinton’s past as a thriving commercial center during the heyday of the timber boom. In more recent times it had since become a centerpiece of the tourism industry, which replaced timber as the county’s economic engine. It was so identified with Marlinton that it adorned the town’s welcome signs.

On March 28, 2008, it burned down. For Bill McNeel, a local historian and preservationist, it was a devastating moment.

“The fire was too awful. It started during the night. Someone driving by saw it, but by the time firefighters got there, it was too late to save it,” he remembers. “But it wasn’t totally destroyed, and talk began immediately about rebuilding it.”

That resilient spirit is typical of the people of Marlinton. The Pocahontas County seat has weathered more than its share of disasters, including the 1985 flood that engulfed the town and deposited four feet of water in the depot.

Within a day of the fire, local volunteers had set up a temporary headquarters for the Pocahontas County Convention and Visitors Bureau, which had been housed in the depot since 1983. Almost as quickly, efforts began to raise the funds to rebuild the depot, which was built in 1901 and had been placed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was a classic example of the standard Chesapeake and Ohio depots built during the early part of the 20th Century.

McNeel, who has chronicled the history of the region’s railroads in his book The Durbin Route, noted that it was logging that brought the section of line known as the Greenbrier Branch up the valley along the Greenbrier River. The building of the depot began an era of prosperity as Marlinton became a hub for freight and passenger travel.

“The operation of Cass is what brought it here,” he explained. West Virginia Pulp and Paper Co. had bought a tremendous amount of timberland in Pocahontas and Randolph Counties. Their paper mill was located in Covington, Virginia. They bought the land for spruce. Back then it was used for paper making. They had to get what was cut on the mountain from here to Covington.”

He said the timber boom lasted about 25 years, but by the 1930s the mountains were pretty much stripped. The mill at Cass continued to operate until 1960, when it was sold off to Mower Lumber Company, which was mainly cutting second growth timber.

Passenger service continued on the line until 1958, and freight service did not end until the 1970s. When the C&O decided to abandon the line, they had to go through a hearing process to convince the Interstate Commerce Commission that the operation wasn’t cost effective.

“They were worried about the state of West Virginia being opposed, so they agreed to donate 92 miles, most of the railway bed (most of which became the Greenbrier River Trail), and all the buildings other than track to the state. So all the depots were acquired by the state,” McNeel said.

The Marlinton Depot was eventually deeded to Marlinton Railroad Depot, Inc., a nonprofit organization formed in 1979. McNeel was a founding member and still serves on the board. MRDI owns the property from the depot along Fourth Avenue past the log cabin.

McNeel credits the dedication of the late Ruth Morgan, an ardent historic preservationist, with finding the funds to convert the depot into what became the Pocahontas County Visitor’s Center. The building also contained railroad memorabilia and for a brief time, a craft shop. However, because the deed said the building couldn’t be used for commercial purposes, the craft shop did not survive.

Until that fateful night in 2008, the depot had served for 35 years as the Visitor’s Center and CVB office, welcoming thousands of tourists annually. But even before the fire forced the issue, the CVB was exploring options for expansion because space in the depot was no longer sufficient to meet its needs. The fire prompted them to go ahead and find a larger permanent location.

Not willing to give up on the depot, the MRDI and local supporters pursued funding to rebuild the depot and to find an appropriate tenant. “We received a large transportation grant, for which the county commission agreed to serve as fiscal agent. Insurance covered some of the expense, and lots of folks gave individual donations. It was a real community effort,” McNeel says.

The Town of Marlinton also became involved, and in 2012 Mayor Joe Smith announced that Alleghany Restorations of Morgantown had won the contract to rebuild to depot to look exactly as it had before the fire—at least on the outside. However, once the exterior was completed, lack of funding prevented completion of work on the interior, and a tenant had still not been found.

After four years during which the building sat vacant and unfinished, the Pocahontas County Artisans Co-op entered the picture. Dawn Baldwin Barrett had just become president of the organization, which was looking for a larger space to house its artisan’s gallery in downtown Marlinton. At the time it was located in the Mitchell Building across the street from the depot, but they were quickly outgrowing the space. Looking across at the depot, Barrett saw an opportunity to benefit both the co-op and the town.

“It was so sad to see it empty,” Barrett remembers. “I talked to Joe (Smith) and Bill (McNeel) about using the depot. Bill said if we would make the commitment to move in, they’d get the interior done.”

Thanks largely to the generosity of McNeel and his wife, Denise, the floors, electrical work and bathroom were completed. The co-op provided lighting and other fittings. The interior work was done by local contractor Andrew Must and his team, creating an airy and welcoming interior tailored to the needs of the artisans.

The Fourth Avenue Gallery of Fine Arts and Crafts opened in March of 2017. McNeel, who spends the winter months in Florida, recalls that his first act upon returning home in April of that year was to head directly to the depot. He was delighted with the transformation that had taken place. In July of that year he was a featured speaker at the dedication ceremony and celebration of the depot’s storied history attended by many in the community who had played a role in its revival.

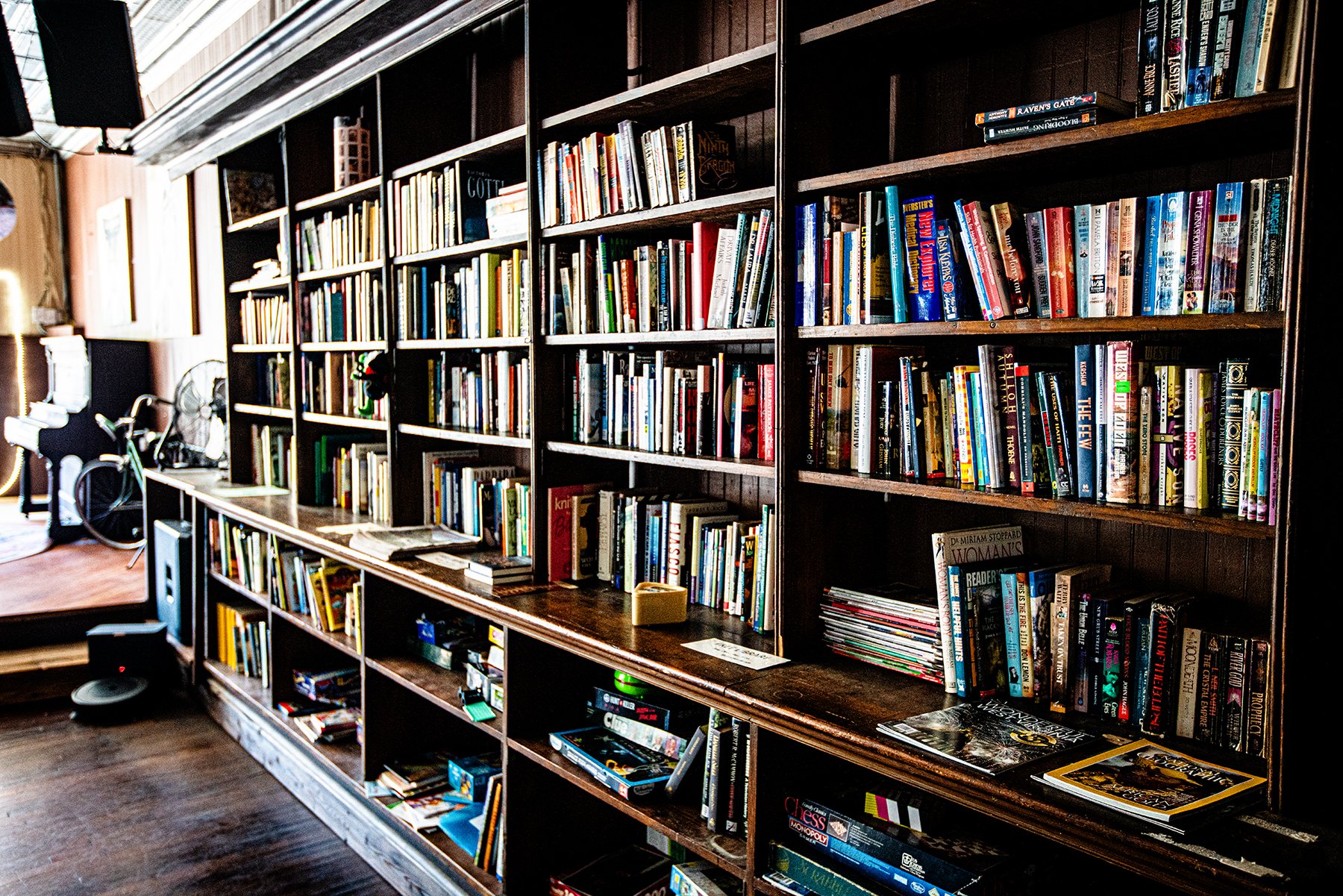

The gallery features works of 40 artisans from Pocahontas and surrounding counties who work in two dozen mediums. Their focus on the region’s arts and crafts heritage has attracted a blacksmith, broom maker, basket maker, stonecutter, several quilters and wood craftsmen making everything from spoons and cutting boards to clocks, scrollwork and fine furniture. The gallery also showcases artists working in watercolor and oil, photographers, jewelry-makers and members creating specialty foods from local sources.

On select weekends throughout the year, the gallery stays open late, hosting local musicians and poets and providing craft demonstrations that transform the gallery into a community gathering place. They also operate a seasonal gallery at The Shops at Leatherbark Ford, located adjacent to the depot at Cass Scenic Railroad State Park.

“We are a nonprofit with a mission to support the arts and arts-based businesses in the community. We also want to help artisans learn more about the business aspects of selling their work,” Barrett explains. “The gallery is run by members, who have to clerk at least once a month. They pay a $30 monthly membership fee, but keep 90 percent of their sales.” In addition to fine arts and crafts, the gallery also carries books about the local area and contains a small collection of railroad memorabilia.

“As of 2018, the co-op is leasing the log house at the far end of the depot property, the oldest structure in the county, from the Historic Landmarks Commission. We’re collaborating with the Art Guild so that both organizations can use it for meetings, classes and exhibitions. The flatbed car could be a stage for performances. With the depot as an anchor, who knows what might happen in that space?” she says.

It took a village, but the little yellow depot is once again thriving, and now more than ever it symbolizes the can-do spirit of the people of Marlinton.

“It’s been so gratifying for all of us,” Barrett says. “The response from the community has been so overwhelmingly positive. The depot is being used for the community. There is so much good will around it being back in use.”

The Fourth Street Gallery is open year-round, seven days a week from 10-6; 10-5 in the winter. For more information, visit pocahontasartistry.com