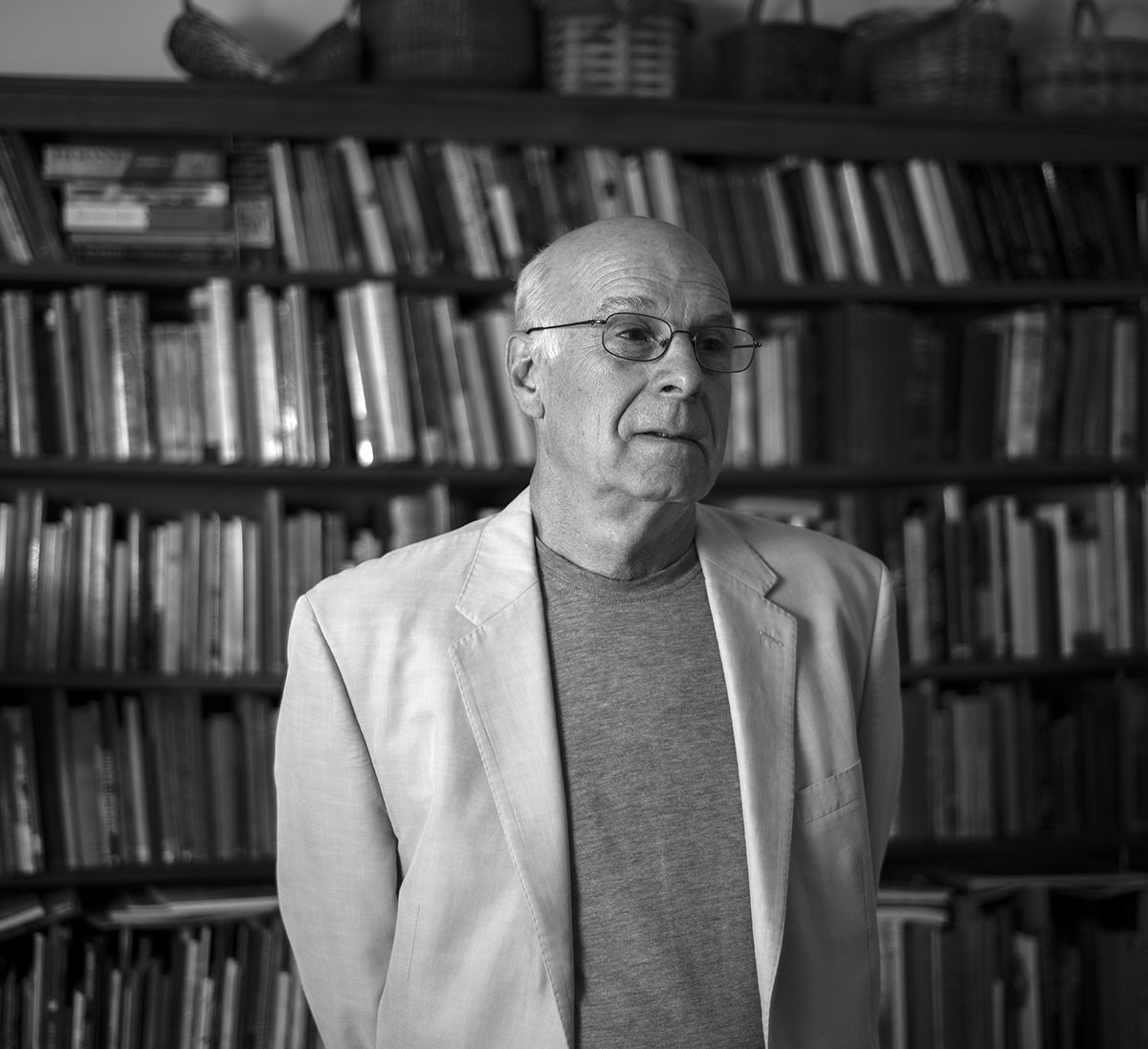

Cameron Little - In Search of a Comfortable Suffering

STORY BY SARAH ELKINS

The first time Cameron Little attended mountain bike practice with the Greenbrier Valley Hellbenders Youth Mountain Bike Team, he hated it. He remembers telling his parents, “This sucks. I’m never doing it again.”

Cam had tried a couple seasons of cross country and he was a talented baseball player, but he hadn’t found the thing that really clicked for him. After that first bike practice when he was just 14 years old, cycling was clearly not “the thing.” But that was 2019. And, as we all know, a lot has changed since then.

“I wasn’t used to the hard work,” he can say now. Mountain biking is a tough sport to get into when your introduction is the infamously rugged terrain of West Virginia. The barrier to entry is multiplied if you happen to live in the Greenbrier Valley where most trails take only two routes: straight up the mountain and straight down the mountain. It’s no surprise Cam wasn’t in love with the idea of hiking a bike up one side of a mountain to come tearing down the other side in a screaming blaze of gravity.

Fast forward four years. Cam is sitting at the kitchen table with his parents. He turned 18 a couple months ago, and he’s fresh off the USA Cycling Gravel National Championships in Nebraska. In the first few minutes of our conversation, he makes quick work of several thick slices of pork tenderloin and a salad. A big bowl of vegetable soup disappears next. “He’s always eating,” his mom, Kris, laughs.

So, how did Cam go from hating mountain biking to being a nationally ranked racer in one of the most grueling long-distance disciplines in cycling? The short answer is COVID. When the world shut down in March of 2020, there was nothing for a kid to do but go outside and play. Cam and his friends rode their bikes to meet up, spending long, empty hours riding around town and to the skate park. They weren’t allowed in each other’s houses, so they hit the road by bike.

With not much else to do when the Hellbenders started practicing in July, Cam decided to give it another shot. He was on a new mountain bike, and he’d been riding every day since early spring. The same trails that had mocked him the year before weren’t so daunting all of a sudden. Without realizing it, Cam had built endurance and power. He’d also lost thirty pounds simply by leaving his house after breakfast and not coming home until dinner. He was a lean racing machine…without a single race on the calendar. The West Virginia Interscholastic Cycling League’s (WVICL) 2020 race season had been canceled, but the Hellbenders continued to practice throughout summer and into the fall months. And Cam kept riding, honing his technical skills and putting in the miles.

In November, Cam sold that first bike, pulled out all the money he’d saved mowing lawns, and bought a full suspension trail bike, the sort of bike that could handle all the roots, rocks and copious mud that puts West Virginia on the proverbial mountain bike map. His first order of business was to take his sweet new ride with its big knobby tires to the Rock Hill Mountain Bike Mayhem, a race in South Carolina.

Cam soon learned the South Carolina mountain bike scene was a little different from the West Virginia scene. There he stood on the starting line in his baggy downhill shorts with a bike built to handle the sort of boulder drops he was unlikely to find in a state with a palmetto tree on its flag. One spectator even blurted, “That kid is on a trail bike!” Cam was surrounded by kids dressed head to toe in Lycra astride sleek XC bikes built for climbing. He’d brought a Clydesdale to a sprint.

The following spring, Cam and his parents took a trip to Sedona, AZ to ride bikes. “That’s when I figured out the adventure of it. I realized how many places I could go on my bike,” he says.

Once home, Cam registered for the Middle Mountain Mama, a punishing cross country mountain bike race that takes place the first Sunday of May at Douthat State Park in Clifton Forge, VA. Along with a small group of riders from Greenbrier County including his Hellbender coach Max Hammer, Cam headed to the race.

Max had been on course for a few minutes before Cam’s group started. Not too far into the race, Cam caught up to Max and a group of other racers. Cam took the pass at an opening and continued up Stony Run. A rider in front of Max muttered that the obviously young rider who had just passed them was sand bagging the race. Max said, “This is that kid’s first ever cross-country race, and I’m his coach.” The rider had nothing more to add after that. The stony silence of that long climb still makes Max grin.

Throughout the remainder of spring and into the summer of 2021, Cam worked landscaping, training and racing when he could. The difficult physical labor took its toll and he found he couldn’t ride as seriously as he’d like to. He began his sophomore year at Greenbrier East High School and raced with the Hellbenders, winning four of the five WVICL season races. Ironically, he took second at Twin Fall State Park because, as he explains it, he couldn’t keep up on the gravel course.

“That year I learned a lot and pushed myself. I’d go for KOMs around town,” Cam says. (KOM stands for King of the Mountain and is a designation awarded to the fastest rider of a particular segment on Strava, a progress and GPS tracking app used by cyclists and other athletes.) Gauging his progress over time and against other cyclists in the area became Cam’s best training tool, but it was clear he needed something more. In 2021, he started working with a professional cycling coach.

“In baseball I had natural talent but I was unwilling to work hard. When I ride, I like to push myself. It was something new that I’d never really experienced before, that type of physical suffering,” he says of cycling. “Also, I realized it wasn’t a team thing. How well I did was determined by myself.”

Cam was zeroing in on what exactly it was about cycling that spoke to him. He seemed to possess a particular desire for pain specific to endurance athletes. Yet, he may never have returned to the sport without the empty backdrop of the COVID pandemic.

“I was able to figure it out in a time where I had nothing else to worry about. I didn’t have school to worry about, and when we went back to school we only went two days a week.”

The unusual training ground of 2020 and 2021 led to what would be Cam’s breakout year. In June of 2022, he traveled with Sam Hawver, another promising, young mountain bike racer from Greenbrier County, to Colorado. The two would spend the coming weeks training at elevation for the USA Cycling Mountain Bike National Championships slated for the third week of July in Winter Park, CO. He placed a respectable 92nd in his first national race and headed home just in time for the NICA (National Interscholastic Cycling Association) season.

By the end of October, he had swept the season, winning all five races in the varsity category. Cameron Little was the 2022 varsity state champion, the fastest youth mountain bike racer in West Virginia.

But, the mud in his treads had barely dried before he had to turn his attention to the next challenge ahead. In December, Cam would undergo the first of two major jaw surgeries to correct a severe underbite. In this first surgery, his palate was surgically broken to allow expansion. The excruciating procedure required a six-week recovery. The time away from training would send him into the 2023 race season at a deficit.

When he got back on his bike after surgery, Cam’s focus had shifted. Cross country mountain bike racing wasn’t the discipline for him. Cam is an endurance athlete; he’d been spending more and more of his time on long gravel and road rides. He couldn’t understand training fourteen hours a week for a race that would last forty-five minutes.

“I have no interest in that,” he says. “I think that’s why gravel racing suits me. It’s a long day of tactics and trying not to burn myself out too early.”

In June of this year, Cam raced his first national caliber gravel race, the North Carolina Belgian Waffle Race, a 79-mile grind with 8,000 feet of climbing. He placed 2nd in his age group and 8th overall in a field of more than 300 racers.

Between a handful of big races, Cam has mostly trained throughout the summer and fall months. These days his training rides look a little different than they did in the free and easy days of the COVID shutdown. His dad, John, explains:

“Ninety-five percent of Cam’s miles are solo. He likes that; he loves that mind clearing, suffering by himself.”

“But,” he adds, “I also wish he spent more time hanging out with like-minded people who have shared goals. No matter what you do, you’ve got to do it with people better than you to progress. He’s not going to find that here.”

That will come in 2024 when Cam will be a college freshman racing for some lucky team. For now, he doesn’t mind spending six solitary hours in the saddle. When asked what he thinks about when out on an eighty-mile ride, he says, “A lot of nothing. I listen to music but it goes in one ear and out the other. I have a lot of meaningless conversations with myself. Or, I might look down and see that I’m going 18 mph and I figure out that it takes three minutes and twenty seconds to go a mile. I do a lot of math while I’m riding.”

I’m not sure that’s the whole answer. Something else is happening when Cam is on his bike blazing past the bison farm in Paint Bank, VA or down a gravel road lined with Queen Anne’s Lace that becomes a white blur at 30 mph. He doesn’t quite have the words for it, I suspect. But, he knows this:

“I’m not pushing nearly this hard in anything other than cycling. But, I think cycling makes me a better person—working hard at things, understanding perseverance. Also, it makes me a happier person.”

“It’s helped him with his surgeries. He knows suffering,” his mom adds.

_____

After three weeks of training and racing in Steamboat Springs, CO in August, Cam headed to Nebraska for the USA Cycling Gravel National Championships. He was at peak performance and went into race day with a cool head. He was hydrated, calm, and dialed. He showed up to the start line early and told himself, “Alright, I gotta use everything I’ve learned this year in this race.”

Off the start, Cam settled in with about 20 people in the front group where he averaged 22 mph for the first 35 minutes. When two guys broke off the front, Cam went with them.

“I was pushing hard to get up there, but I thought this is a comfortable pain, a comfortable suffering. I’ve learned there is a type of suffering I enjoy a little bit, a comfortable suffering. I thought, if I feel like this all day long, I’ll be good.”

Eleven miles into the race, the lead peloton crested a hill then dropped into a left-hand turn with sandy loose gravel. Cam was blinded by a big cloud of dust blocking the view of what was ahead.

“Next thing I knew, I was in the ditch,” he says. He’d slid off the road, crashed, and hurt his hand.

“I had been stopped for like four minutes and thought about withdrawing. Another kid on the ground was really hurt and screaming. I thought I’m not that hurt; I can keep going.”

By the time Cam was back on his bike, he had lost the peloton by five or six minutes. He would ride the majority of the next 77 miles alone, battling the dust and wind in the stark Nebraska landscape without the benefit of a draft line, trying to mute the searing pain in his hand.

“It killed me mentally, but all I could do was keep eating and push on.”

In the end, he finished 11th—11th in the nation, a noble place among the best riders in the country, but Cam isn’t satisfied.

“I haven’t had a solid race this year where I could execute my plan,” he says. “I haven’t been able to see where I stack up against these other riders. I’m curious how good I am against them.”

It’ll be a while before he gets his answer. Cam is preparing for his second and even more invasive surgery as this story goes to print. All of this in the midst of college applications, SAT and ACT tests, high school, and the extra college courses he’s already taking. It’s a busy time for any high school senior without the added stress of major surgery and a looming race season.

“Until surgery, I’m focused on having fun,” he says. “This weekend I’m riding the whole river trail up and back. I don’t know if that will be fun, I’ve never done anything that long. But, because there’s a target I’m going for, the KOM, I can make that fun in my mind.”

The Greenbrier River Trail is a 78-mile-long rail trail that follows the Greenbrier River north from Caldwell to Cass, WV. Tourists frequently ride the trail from one end to the other over a couple of days with bed and breakfast stays in between. Cam is riding up and back, 156 miles total, in what he thinks will take somewhere between six and seven hours. (It will be worth downloading Strava to your phone just to see the KOM he is bound to possess by the time you’re reading this.)

After surgery, Cam says, “it will be about getting back in the gym and focusing on what I need to do for 2024.” Right now, he doesn’t have any races on the calendar, but you’ll likely find him on some podium in spring. In the meantime, he’s doing the math, finding that comfortable suffering.