Homesteaders' Homecoming

By Barbara Elliott

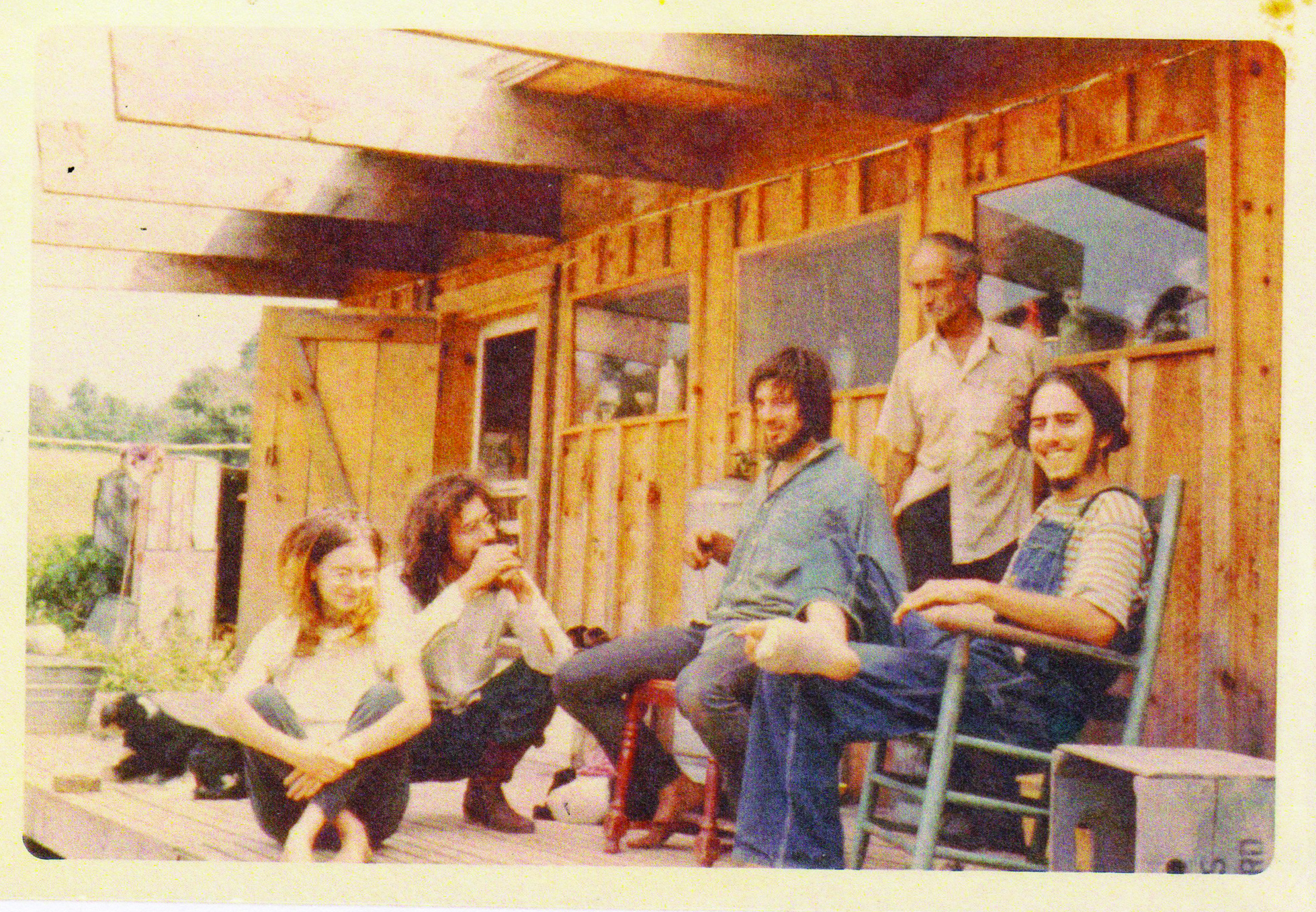

The Greenbrier Valley Quarterly invited a small group of the “hippie homesteaders,” who migrated to Greenbrier and Pocahontas Counties in the early 1970s, to reflect on the ways their decision to live off the land shaped their lives, and how in turn their presence changed the Greenbrier Valley forever.

It was really all about the land. The availability of cheap land was the siren call that brought young, college educated urbanites to try their hand at living off the land in the Greenbrier Valley in the early 1970s. There were other factors that played into their decision to forego such luxuries as central heat, running water, and indoor toilets, but the common denominator was a desire for land of their own on which to live a simple, healthy lifestyle unfettered by the rigors of a nine-to-five existence.

A few of these “foreigners,” as some locals dubbed them, began arriving in the late sixties, but it was in the early seventies that van loads of latter-day pioneers began to inhabit abandoned farmhouses and log cabins tucked back in hollers where farms that had been family owned for centuries were struggling because members of the younger generation were moving away to find work.

Although some of the new arrivals truly hoped to actually live off the land, for many the decision to move to West Virginia was less quixotic. The turbulence of the times and the Vietnam War played into the homesteader movement, but for the small group of veteran homesteaders who shared their experiences for this story, their reasons for coming were as varied as the paths that they eventually took after arriving. For some it was just a youthful lark, for others an effort to escape a lifestyle they did not find fulfilling. But all agreed it changed their lives forever and for the better.

Barry Glick, at the time a self-described “tripped out hippie living in Philadelphia,” found West Virginia purely by accident when he spotted an ad in the Philadelphia Inquirer offering 58 acres of land for $6,000 in July of 1972. He thought it was a misprint. When he discovered it was for real, he drove down to check it out and quickly discovered the joys of driving between Lexington and Covington before Interstate 64 was built. He bought the land, rented a house until he could build his own, and developed a business growing a lucrative “medicinal herb” that was in great demand back in Philly. He eventually started the Almost Heaven Hot Tubs factory in Renick, with his partner Bob Hoffa, which they later sold. Today, he still lives on his 58 acres in northern Greenbrier County where he operates Sunshine Farm & Gardens, a purveyor of perennials, bulbs, wildflowers, shrubs, and other plants that he markets around the world in addition to lecturing about West Virginia native plants.

Carolyn Rudley was a single school teacher living in Pittsburgh when she visited friends in the area and asked if they could introduce her to any single men. The next day at a party she met Alan Rudley, a childhood friend of Glick’s whom he had persuaded to purchase land near his place. Before she knew it, she and Alan were sharing a log cabin with no running water or heat.

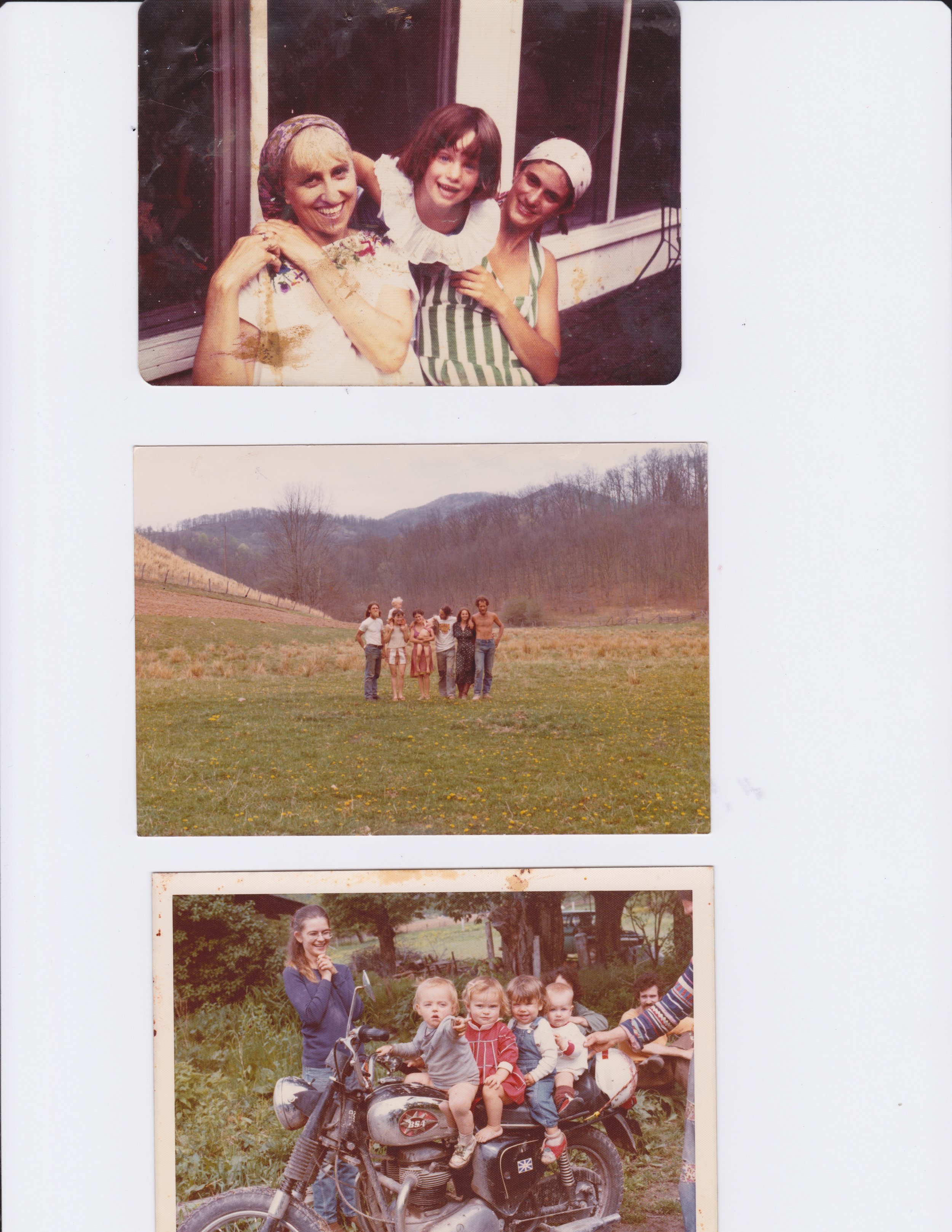

Most closely fitting the stereotypical profile of hippie homesteaders were Rikki Peters and Chally Erb, who in the early seventies were living in a communal flat in the Haight Ashbury neighborhood in San Francisco, ground zero for the counter-culture movement. Rikki had lived communally since she was 16, including a stint at the Wheeler Ranch in Northern California. She gave birth to her daughter, Deva, in 1972 at age 18. Not long after, when a visitor suggested they try West Virginia, Chally bought an old bread truck, and the threesome moved to one of the original and most famous communes in West Virginia, The Red Hood in Summers County. The commune eventually moved to the Jacox area along the Pocahontas/Greenbrier County border, and they moved with it.

Beth Little was also living in California, but in very different circumstances. She and her then-husband, Bill Huffman, had two children and were living a middle class life in Los Angeles. Bill worked night shift at the phone company, and Beth did computer programming from home. Bill had been with the phone company long enough to get three weeks of vacation, and the family would camp on the Colorado River or along the Oregon Coast. “It was never enough,’” Little remembers.” It was worse and harder to come back. We decided to take a year and find out how long it took to get tired of being on vacation.”

To that end, they sold their house, rented a tiny apartment, and Bill began building a house on wheels in which they would travel for fourteen months. They had saved up $5,000—a lot of money back then—especially since gas was thirty cents a gallon, Beth notes. Along the way, they discovered West Virginia. By then, they knew they weren’t going back to California. They settled in the Lobelia community in Pocahontas County, where they moved into an abandoned farmhouse they dubbed Melvie’s Mansion because it was owned by Melvin Hill. It was so dilapidated that Mr. Hill would not take any rent for it.

Cathy and Danny Boone were living outside of Richmond when they visited Greenbrier County, where Danny’s parents had grown up, so that Cathy and their infant son, Dylan, could meet the extended family. Danny had giving up a lucrative career in retail management in a high end department store because he disliked the money-driven culture. He had always been interested in teaching, so he had taken additional courses to earn a certificate to teach English. By the time of the visit, Danny said the “idea of raising children in the city didn’t make sense anymore,” so when his great grandmother’s house was offered rent-free, the young family headed west. Danny didn’t have a job lined up, but at the time, that didn’t seem to matter.

Michael Rosolina and his then-wife, Amy had first experimented with homesteading in Tennessee and Virginia, where they had become acquainted with Dave and Rose Burhman, who eventually settled in the Friar’s Hill area of Greenbrier County. They liked what they saw when they came to visit the Burhmans and decided to look for land of their own. In the beginning, they rented a house with wood heat and indoor plumbing, which was step up from the place they had lived in Tennessee. Of course the rent in Tennessee had been $25 a month, and in Greenbrier County they paid $50.

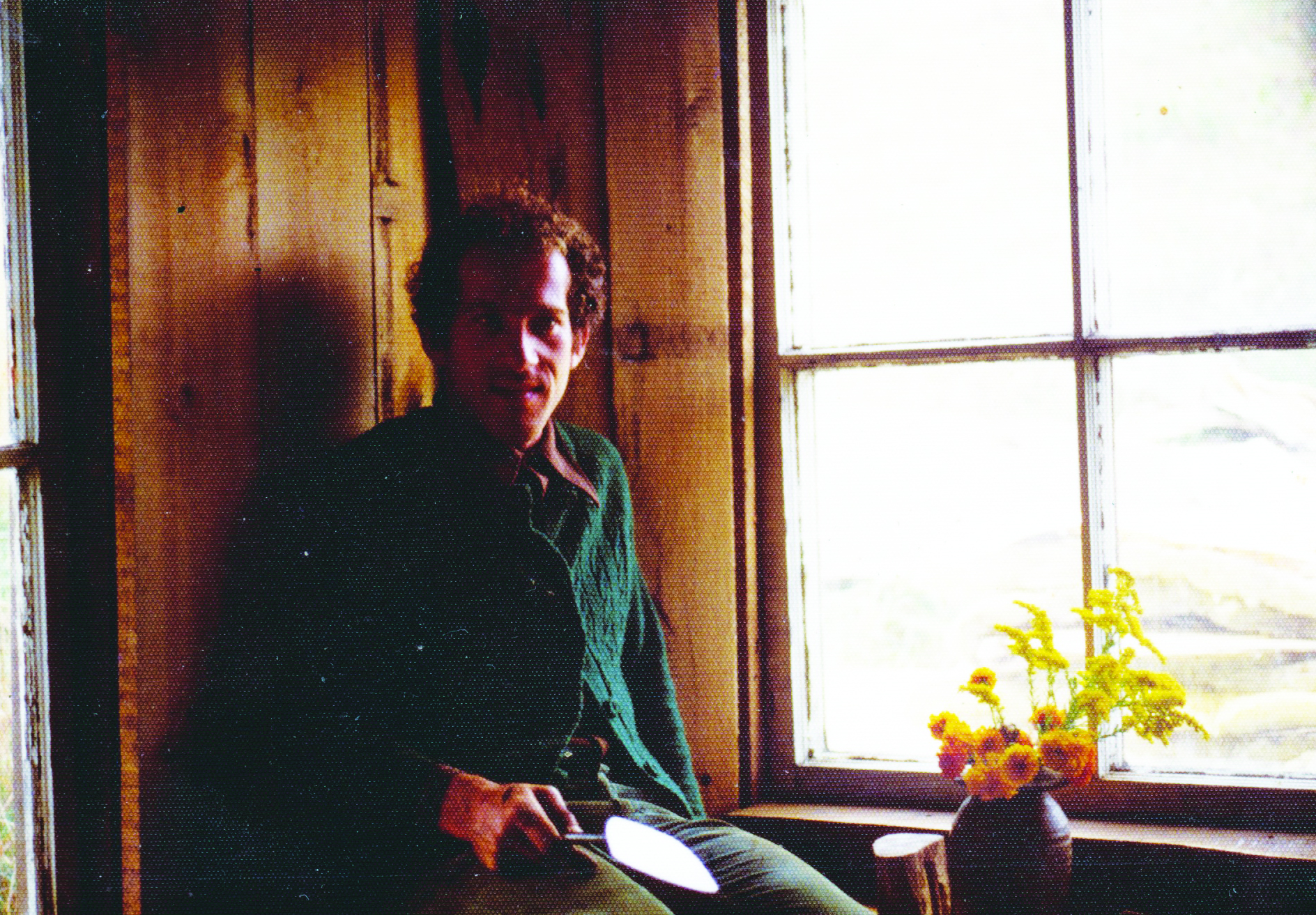

Stephen Jackendoff was a chef at a restaurant called Wildflower in Philadelphia when he began dating Nikki Coates, who had lived at the original Red Hood. In August of 1975, they visited the relocated commune, and he loved it. He went back to Philadelphia, gave his employer seven weeks’ notice, and in October he moved into a locust post barn at the back of the commune and used a chain saw to cut holes in the walls for windows and for a wood stove chimney pipe.

The new arrivals quickly found that their existence centered around the basic elements of life-- water, heat, and food--and for the most part they were clueless about all of them. Fortunately, through the generosity and kindness of older neighbors who took the starry-eyed newbies under their wings, they soon learned how to chop wood, plant gardens, care for livestock, eat native plants, can food, and build a haystack that repelled water rather than absorbing it.

“We had a woodstove, and we didn’t know how to build a fire or do anything,” Cathy remembers. “Danny’s family were around and helped me figure out how to conserve water. I thought you turned it on and it never went away. It was learning how to survive in a foreign environment.”

Collecting and conserving water were important skills. Stephen recalls that they would use the water to wash dishes, then wash the floors, and finally water the flowers. There were always at least three uses for water, most of which came from springs and had to be hauled in buckets to the house. “Everybody had yokes for hauling water,” Rikki says, and Cathy remembers taking showers under rain spouts.

Gathering enough firewood to heat the drafty old barns and farmhouses was another challenge. Barry remembers braving the cold in his pajamas at 11 p.m. to cut up a rail fence for firewood. “If it had not been for our neighbors, the Blankenships, we would have died,” Carolyn says, recalling that during the first winter in the log cabin he she had to spike her coffee with whiskey to stay warm. “Things would get pretty dire, and then the neighbors would show up with a load of firewood.” They also shared their wisdom on surviving in the country.

“We had sheep, and after the first snow we got a phone call on the nine-party line, and our neighbors said, ‘have you seen your sheep,’ and we said, ‘come to think of it, we haven’t.’ There was a very long pause, and finally they said, ‘well you know, sheep don’t come down in the snow. You have to go out and get them and make a path for them.’ It was just little things like that we had not a clue about what to do,” she says.

The reason for their acceptance by the neighbors had a lot to do with mutual dependency. “A lot of our neighbors had children our age who had moved away, and they were so happy to have people come by, because all of a sudden they had someone who could tell them their cows were out,” Stephen recalls. “We learned a lot of from them, but they also had people to help them cut hay.”

Michael agrees, adding, “They were getting on in age and their children didn’t want to live here. We wanted to know how they did everything. How could they not like us?” He added that fellow homesteaders like Heike Fey and Janet Friedman, very early arrivals in the Friars Hill community, were very helpful to their new neighbors.

Beth Little turned to the Pocahontas County extension agent, Betty Weiford, for advice on gardening and canning, and a bond quickly formed. Betty put together workshops where the homesteaders went to share recipes with the local ladies, and she even visited Melvie’s Mansion. Beth had a serious interest in organic foods and planted vegetables on a plot that had lain fallow for many years. Word of her amazing garden soon spread among the locals, who couldn’t believe the bounty she was producing.

Many of the homesteaders did not have vehicles (or in the case of The Red Hood, shared one or two vehicles of questionable reliability), so trips into town for groceries were not common. Fortunately, those were the days when Hale Arbuckle’s food truck still ran regular routes in the northern part of Greenbrier County and southern Pocahontas County, delivering grocery staples and other necessities ranging from kerosene and medicine to the Sunday New York Times. His kindness to the young newcomers was legendary. Stephen, who in those days traveled mostly by foot or horseback, recalls catching rides up Highway 219 on the running board of Hale’s food truck, the truck being too packed full of merchandise to fit another person.

“A lot of them moved in with the idea they could have an acre of land and make a living off it. As A farmer, I knew better,” Hale Arbuckle says. “People called them hippies, and they all seemed to know each other. They were fine people, honest people. I don’t remember ever losing an account to any of them. They became personal friends of mine.”

As the homesteader community grew, The Red Hood and Melvie’s Mansion became way stations for newcomers, who would stay there until they could find land of their own. Stephen laughingly recalls that there must have been ten copies of Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet and Molly Katzen’s Moosewood Cookbook in the barn at the Red Hood.

Despite the acceptance by some of their older neighbors, the hippies still found living in a commune in rural West Virginia a challenge. “I was stuck on this commune with what I considered old people. We had long hair, and pierced noses, and tattoos. The local people couldn’t even talk to me, plus they couldn’t stop staring at my nose ring,” Rikki remembers. Michael adds, “The locals thought we were all a bunch of pot smoking hippies—and they were right.” However, he theorizes that a shared enjoyment of moonshine and mountain music helped bridge the divide. The tradition of moonshining in his neighborhood made folks a little more tolerant than they might have been otherwise, he suggests.

Rikki and Chally had actually decided to leave, but they wrecked the Red Hood’s Scout before they could take off. They stayed because the commune needed their bread truck. It was a twist of fate for which she is now grateful. Living at the Red Hood she learned to bake, a skill which would eventually give her a means to make a living. Today, she recalls the fall she spent canning the bounty of the garden and hanging out with her daughter at the original Red Hood as the happiest season of her life. “It was great for kids. That was the ultimate decider. Deva was a different child here,” she says.

Relationships with other members of the Red Hood could also be tense. “You couldn’t live the way we were living and not have a little bit of moxie,” Stephen notes. “You were living a very different way. You couldn’t turn on a light switch. Food didn’t come from the store.”

Over time, the stresses of communal living took its toll on those living at the Red Hood, and eventually the core group that had bought the land divided it up into parcels and moved onto their separate homesteads. Relationships ended, new relationships formed, some of the early arrivals began to leave as the realities of living off the land sunk in, and many of those who stayed faced the fact that they had to find a way to earn money to survive.

Beth Little went so far as to return to Philadelphia for seven years. By that time she was a single mother, so the security of job as a programmer at the University of Pennsylvania was a draw. Even so, flights of geese overhead would make her terribly homesick for the country. She was eventually accepted to graduate school and offered a full scholarship. Although the advanced degree would have given her opportunities to make even more money, she ultimately realized that the work would be for someone else, and she wanted more freedom and flexibility with her time. She came home to Pocahontas County. Fortunately, her decision to move back coincided with the arrival of home computers, and she was able to carve out a career for herself helping others adapt to the new technology.

Before he became a teacher, Michael would leave for long stretches of time to work on large-scale construction projects like the construction of a dam in Bath County, Virginia and high-rise buildings in Washington, D.C. He recalls that in Washington, the crew was about one-third African American, one-third Hispanic, and one third from Appalachia. “It’s the Appalachian tradition to have to go somewhere else to make money,” he says.

Even with the disruptions, arrivals and departures, a close-knit community developed among the homesteaders. They began holding annual gatherings which started out as a forum for sharing the wisdom they were gaining on how to live off the land. “At first we actually had people teaching gardening and canning. There were music workshops. It was really about learning,” Rikki says. The gatherings eventually evolved into a sort of family reunion, where those who stayed and those who had moved on came together for a day of good food, music, dancing, and fellowship.

The homesteaders loved to play music, and they quickly embraced the old-time tunes they discovered in the West Virginia hills. Because of the distances between the homesteader enclaves like Friars Hill, Jacox and Lobelia, parties were at a minimum overnight affairs. “Every time there was a gathering, everyone was playing live music, old-time mountain music, and it was charming,” Michael says.

In the four decades since the first wave of homesteaders arrived, many have moved on. But those who stayed have found their lives enriched many times over by the beauty of the land and close community that developed among the newcomers, and eventually between the homesteaders and the locals. In turn, the homesteaders have contributed in countless ways to the offbeat charm that gives the Greenbrier Valley its unique vibe.

Danny recalls that when they arrived, Lewisburg’s eateries were of the “pork chop and gravy” variety. The late Gwen Clingman’s down-home cooking was the highlight. Carolyn recalls that the only excuse for bread was maybe Roman Meal. “I learned how to make my own pasta, my own yogurt, my own bread,” she members. Cathy laughs when she remembers sending her sons off to school with carob for a snack. She eventually learned that they were trading it with their classmates for Hostess Cupcakes. “They wanted chocolate and sugar, and we gave them carob and honey,” she laughs.

The culinary landscape began to change by the early 1980s, when lunches featuring exotic ingredients like tofu and sprouts could be found at the Up Top Sandwich Shop, an enterprise operated for a time by Ginger Must, Heike Fey and Beth Little, in a space above what is now the SPH Interiors gallery in downtown Lewisburg. “It was the first restaurant for us,” Carolyn says. Stephen opened the Cardinal Restaurant, where he hired Rikki to put her newly learned baking skills to work. She later started the Bakery on Court Street, and her bagels were eagerly adopted by the locals, even if they did call them “beagles.” The tradition she began of fresh baked goods and sandwiches and salads made with fresh ingredients continues under the current owner, Lisa Carter, the daughter of Janet Friedman. The demand for organic ingredients resulted in the opening of a health food stores in the location where Peddler’s Antiques is today before Edith McKinley opened Edith’s Health Food Store. It started out in the space currently occupied by Studio 40 before moving to its current location on Washington Street.

As they became more integrated into the larger community, the homesteaders left their mark in other ways. Danny, Michael, and Carolyn became teachers, and each has now retired after more than 30 years of service in the Greenbrier County Schools. Danny also is a veteran performer with Greenbrier Valley Theatre and feels blessed that such a vibrant theater existed in Lewisburg even in those early days.

Others like Barry became entrepreneurs, opening businesses that have flourished and contributed to the economy of the area. They founded nonprofits like the Family Refuge Center, the domestic violence agency that serves the Greenbrier Valley, and Allegheny Mountain Radio, the community radio station that serves Pocahontas County. They played a major role in Lewisburg’s emergence as a celebrated arts town. They joined forces with locals to advocate for the renovation of Carnegie Hall in the early 1980s and have remained active as volunteers and instructors at Carnegie Kids’ College and its Creative Classrooms in the schools. Trillium Performing Arts, which has sponsored workshops and dance performances for more than 30 years, had its beginnings at a homesteaders gathering. Beth White, an early resident of the Red Hood, and Carli Marenek, who raised her family on the land in Monroe County, are two of the founding principal artists of Trillium and have taught dance to generations of Greenbrier Valley residents.

Their appreciation for the timeless beauty of the area and the lifestyle they enjoy here has occasionally motivated them to advocate to save it. Barry remembers, “The first thing the Lewisburg bluebloods and the straight people and hippies all agreed on was we didn’t want Walmart. Nobody wanted Walmart.” On that one, they lost.

Beth Little did not set out to become an environmental activist, but she was horrified to learn that there were plans to build a dam above the Falls of Hills Creek to make a lake or campground. When she attended a public meeting where a scientist explained the impact that the plan would have on the unique and delicate Cranberry Bogs, she spoke out. She has since become a leader in the West Virginia Nature Conservancy’s efforts to preserve the natural beauty of the state.

Although the homesteaders have largely become integrated into the community and quite a few moved to town as their children entered school or as they grew older, they retain their love of a more natural way of living, a pride in the self-sufficiency they learned from their early experiences, and an affection for the unique community they helped forge. All agree that the benefits that have accrued to them from their decision to move to West Virginia greatly outweigh any obstacles they had to overcome. The greatest of those benefits, they say, was being able to raise their children in a safe place where they could spend meaningful time with them as they were growing up. Many of those children have stayed in the area and are now making their own mark as business owners and entrepreneurs.

In addition to his career as a teacher, Michael has fulfilled his original dream of having some land and doing something with it. He planted an orchard on his Friar’s Hill spread and has nurtured it for many years. He and his wife, Judy, sell their apples at the Lewisburg Farmer’s Market, which is part of a robust local foods movement in the Greenbrier Valley that had its genesis in the desire of the homesteaders to eat healthy, organically grown foods.

Beth Little, who still lives in an energy efficient house she built on her land in Lobelia, says “I have a sense of home and place and community that I didn’t expect to have before this. In a city, I just didn’t have the sense we have here. It’s really special.”

For Cathy, living on the land was all about healing. She had just undergone treatment for thyroid cancer when they moved to Friar’s Hill. “For me, it was all about getting healthy, about making our own bread, carrying water, about building relationships. I was surrounded by love and beauty. In Richmond, life was polite. Here it was not polite. It was confrontational. But I remember the first time someone hugged me with their entire being—full of love and spirit, in a deeply caring way. There was an essence to life and living that had faded away. The greens were greener. The air was cleaner. The stars were there. Everything was more vibrant here. It fed your soul.”

All agree that their dependence on each other and their neighbors had a lot to do with the sense of community that developed among the homesteaders and between the young arrivals and their neighbors. Danny laments, “That’s what’s lacking in town. You are surrounded by more people, but you don’t need each other as much.”

Even with that loss of that intense connectedness that characterized their early life as homesteaders, Carolyn points out that it was the self-reliance forged by their life on the land helped them join hands with the locals to transform Lewisburg into the kind ofsmall town that garners national accolades for its coolness. “The things we learned in order to survive moved forward with us. We made ourselves survive, so we can make a community survive.”