Educating the Whole Child in the Hills of Appalachia

STORY BY QUINCY GRAY MCMICHAEL

Thirteen preschoolers are flying in a spaceship made of tiny wooden chairs, pillows, and blankets—when it chugs to a stop, somewhere between Mars and Saturn. But the kids aren’t distressed. They’re the ones who’d decided it would break down—because what’s more fun than zooming through the solar system with a passel of classmates? Working together to solve a complex mechanical problem at zero gravity, using nothing more than a potato masher and a little kiddo ingenuity.

This is Greenbrier Community School. This is what longtime teacher Mariah Miller means when she talks about “making learning visible.” In her Monarch classroom, students from ages three to five not only experience hands-on learning, they each have a hand in determining what they will be learning. Mariah and her co-teacher Brooke Kelley observe how their students respond to prompts—both structured and spontaneous—and allow the kids’ collective interest to guide the curriculum.

About a week before their spaceship broke down mid-flight, Monarch students were immersed in a study of the rainforest—exploring sloths and snakes, and reading rainforest books. Until one of the kids brought a toy spaceship to school.

Brooke and Mariah immediately noticed a change in the games the kids were playing—“which is when you know that [something has] really sparked their interest. . . if their games start using the vocabulary of a study,” says Mariah. “They lined up the chairs and made rocket ships and got dressed up. . . so we quickly wrapped up with the rainforest.”

The entire Monarch class had boarded that spaceship and taken flight, rocketing away from the dank heat of the rainforest, ready for a new adventure even further from home. And what did the teachers do? They hopped aboard, carrying space books and creative tchotchkes for the kids to use in their imaginative play.

This is Greenbrier Community School, where children are the curriculum.

The Heart of All Learning

“We’re on the cutting edge of education. We’re using best practices for teaching children; our faculty studies child development. . . we are teaching our students to be civil with one another, to problem-solve, be creative and collaborate,” says teacher Toby Garlitz. But how to teach civility and collaboration to a two-year-old, or a twelve-year-old? Treat them with respect. Let them witness peaceable interactions between adults. Children learn from watching, so Greenbrier Community School instructs students by practicing balanced interaction. Teachers and staff take care in their dealings with each other, as well as with their students, because this sets the tone for the kids and establishes the culture of the school itself.

This is Responsive Classroom, which has remained a guiding philosophy since the school’s inception—“the framework in which we manage the classrooms on a day-to-day basis,” explains Rece Nester, Head of School. Responsive Classroom is how “the adults communicate with the children. It’s how we handle any discipline issues. It’s also how we celebrate the children. This is possible thanks to our 8:1 student-teacher ratio and multi-age classes that allow the students to progress at their own pace, learning from one another.”

While the practice of Responsive Classroom is structured around seven principles, its ideological keystone is that a school’s “social curriculum is as important as the academic curriculum,” an idea founded on the fact that social interaction spurs the most cognitive growth. Because of this, GCS values how kids learn as much as what they learn by prioritizing social skills like cooperation, assertion, responsibility, empathy, and self-control. In the classrooms, teachers not only know the children—both culturally and as individuals—but they get to know their families as well.

Just as Responsive Classroom guides children toward social intelligence, the Reggio Emilia philosophy encourages creativity and innovation. Reggio Emilia “sees children as capable learners,” says Rece. “We create a Reggio-inspired school by ensuring that our classrooms feel like an extension of home. They are filled with educational materials that will inspire learning—lots of loose parts to kindle creativity and deeper questions.”

Teachers at GCS design their classrooms with intention, in ways that encourage interaction and exploration between students, mindful of the words of Loris Malaguzzi, founder of Reggio Emilia: “What children learn does not follow as an automatic result from what is taught, rather, it is in large part due to the children’s own doing, as a consequence of their activities and our resources.”

Or, as parent Lara Edwards notes: “One of the things that has really set this school apart is the hands-on learning. The kids learn things, and then they get to practice them with small-table groups and practical applications. And so they’re learning, but they’re also practicing communicating and relating to one another and building skills that are going to serve them so well in life.”

At the beginning of each school year, GCS dedicates six weeks to the work of community-building inside the classroom—time for the students to develop relationships with their classmates and teachers, and to create a unique classroom promise designed by the students. These bonds form the foundation of each class, becoming a comfy carpet on which the children will play and learn. Teachers take their time with this important work, knowing that each student defines both self and their place in the world through essential interaction with others. Classroom community sets the stage for that magic to happen.

The Whole Child

At Greenbrier Community School, learning is a collaborative effort. Starting in the Nido classroom, students as young as eighteen to thirty-six months are active participants in their own education. “We do everything through play,” says Toby Garlitz, who leads the Nido classroom with the help of two co-teachers. “Play is the work of the child. When we are doing numeracy, we [count seashells], we use songs. . . we use nursery rhymes for early literacy. We read, read, read. Anytime a child wants to read a book, one of us will sit down and read.”

After Nido (which means “nest” in Italian) children move to the Monarch classroom, where spaceship-play is only an inspiration away. Mariah, who not only teaches Monarch students but serves as Assistant Head of School, explains that, in these first two classrooms, “the children are the curriculum and academic goals are. . . achieved through games and short experiences—not worksheets.” The students lead their own learning, as their actions and excitement indicate what inspires them.

“In the kindergarten through middle school classrooms,” says Mariah, “the children may not have as much input into the topic but they have a lot of input into how the topic is explored. They are given lots of ways to make their learning visible.” Part of how students exemplify their learning is by teaching other students. In the Reggio Emilia philosophy, the parent is the first teacher, the schoolteacher is the second, and the classroom is the third teacher. At GCS, where learning is a constant, mutual activity, perhaps the other students could be considered the fourth teacher.

This cooperative attitude means that science and social studies curricula are project-based. Students do research, then instruct the other children about what they’ve learned—first the rest of their class, and then the entire school. This means that, if fifth and sixth graders in the River classroom are presenting, students as young as first and second grade (the Beehive classroom) will be learning from them. Afterward, each child reflects on what they learned and reports that knowledge in a developmentally appropriate way.

In contrast, English Language Arts is taught via differentiated instruction—so what each student studies is based on personal learning style, skill level, and pace. Students then rotate through the classroom, independently or in small groups, engaging with the content in a variety of ways during each class period. “We look at every child individually,” says Toby Garlitz. “We really try to meet them where they are, build them up, and scaffold on what they already know.”

According to parent Dylan Boone, GCS offers his daughter, a third grader, the “combination of a high academic standard and the ability to be a kid, to grow and develop at [her] own speed.” He says that the iReady diagnostic program (which assesses students in math and reading three times per year) helps him remain confident and informed about her academic progress. Teachers monitor the students’ iReady progress daily, attentive to any challenges. Like other GCS parents, Dylan relies on iReady “because it’s a national standard [and GCS’s test results prove] that you can teach in a [differentiated] manner and incorporate lunch outside and play and children being able to explore some of the things that they’re actually interested in, as opposed to ‘everybody has to learn the same thing at the same time.’”

Thanks to iReady, three progress reports, two conferences, and an annual standardized test reported to the West Virginia Department of Education, GCS is able to offer parents the assurance of academic excellence within a dynamic learning environment.

Becoming a Community School

When Greenbrier Community School was founded in 1999, it was called Greenbrier Episcopal School. Now in its twenty-fifth year, this small, independent school offers individualized instruction for students as young as eighteen months of age and will soon expand through eighth grade.

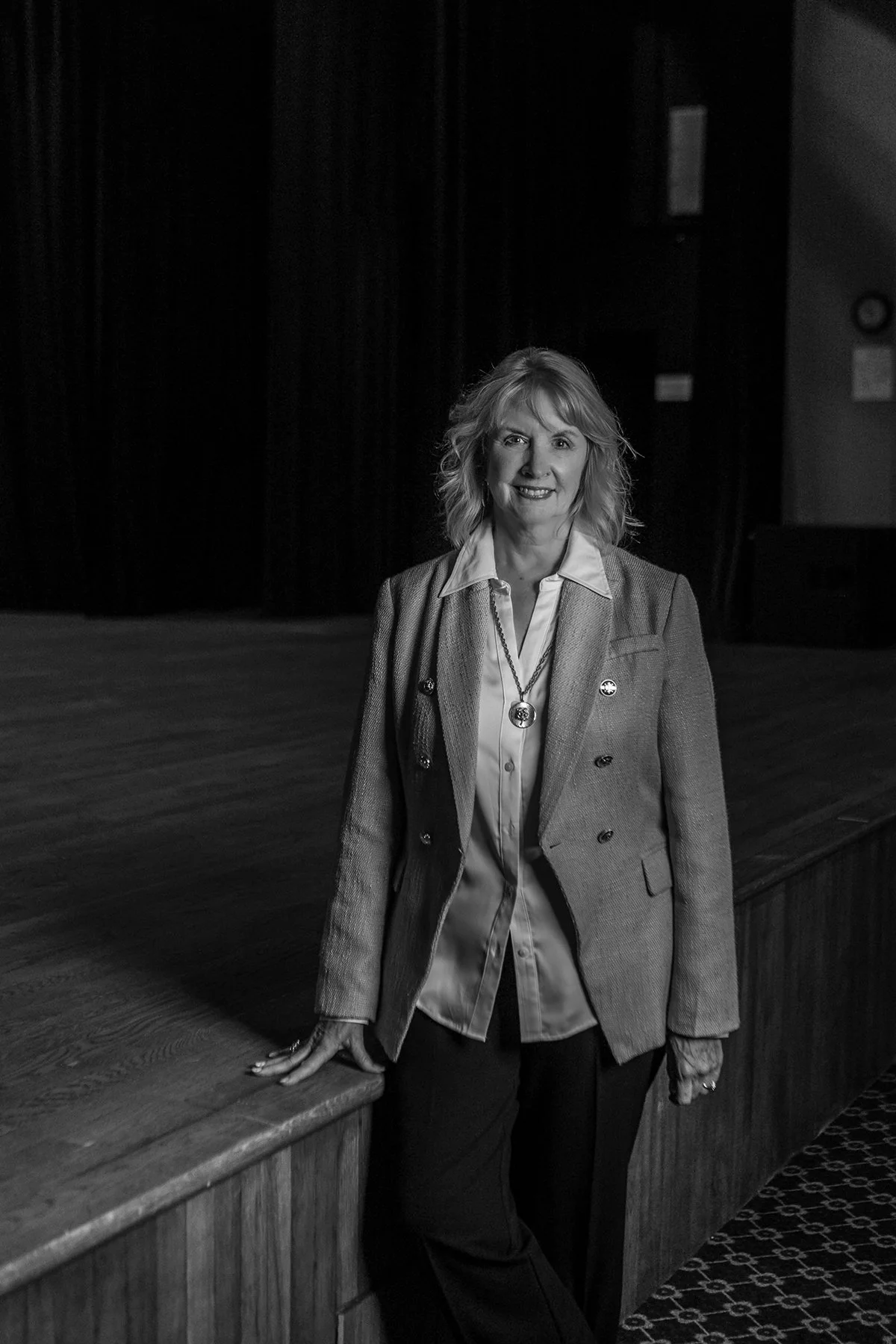

According to Rece, GCS “has evolved in so many ways. . . [eventually] becoming a community school.” She should know. Rece first became involved with the school when she taught sixth grade there in 2009; she returned as a parent, then served on the Board of Trustees before becoming Development Director in 2017—and Head of School two years later.

In 2019, the school chose a name that reflected its mission and vision, becoming Greenbrier Community School. Just months before, GCS had purchased the historic yet dilapidated Bolling School building—which, during segregation, had been the only African American high school in Greenbrier County, West Virginia.

Janice Cooley, a community-minded neighbor, Bolling School alumna, and GCS Board of Trustees Member, says that the “school [building] was practically falling down. . . really in a bad state. When Greenbrier Community School took on the building. . . it gave it new life.” During the eighteen-month restoration of the Bolling School site, awareness of the surrounding community sparked an opportunity for GCS. As the newest member of an historically Black neighborhood, the school began examining its internal demographics.

Four years on, thanks to collaborative efforts between Greenbrier Community School, its neighbors, and Bolling School alums, GCS announced the Bolling-Clay Scholarship. The scholarship, which is awarded to ethnically diverse students, was launched in 2023 to support inclusion and diversity at GCS—and as a way to honor the legacy of the Bolling School. “We think [the Bolling-Clay Scholarship] is going to be extremely valuable not only for the [recipients] and their families,” says Janice, “but for all of the students that are currently at Greenbrier Community School to be able to learn about diversity and learn about the differences that we have in our community. Communicating with people that may not look like [them] is going to be extremely important as they go into the world.”

Greenbrier Community School has also found ways to encourage matriculation among students from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. 54% of GCS’s seventy-one students receive at least one form of scholarship—the state-sponsored Hope Scholarship, the Bolling-Clay Scholarship, and/or internal tuition assistance. Greenbrier Community School recognizes that diversity is a precursor to vibrancy, so the school is doing the work to become even more dynamic, an accurate echo of the community.

Dylan remembers growing “up in the public education system in Greenbrier County when there were multiple junior highs; there were schools in each community. And there was a relationship between. . . the students and the teachers and the parents. And [GCS] feels like that in an era where those little [community] schools have gone away.”

Natalie McClelland, who teaches kindergarteners in the Forest classroom, agrees: “We are a community school. We open our arms and become so invested in anybody who comes to this school. . . all of our kids see it. . . It’s a culture. And I’m proud to be [part of] a culture that shares kindness and love and opportunity for those [who] maybe don’t always feel that.”

One simple way that Greenbrier Community School makes this open-hearted goodwill manifest in the greater community is through the afterschool program—billed as “a place for exploration and relaxation” where “kids can express themselves through play.” The best part? It’s not just for GCS students—all kids are welcome. Any student can take the school bus from Lewisburg Elementary and be dropped off at the front door of GCS for an afternoon of peaceful creativity, under the supervision of innovative and attentive teachers.

A School That Feels Like Family

Over sixty years ago, when the Bolling School was still in session, most educators weren’t talking about children as curriculum. Kids didn’t have laptops; they walked to school, swinging books on straps. Yet, the memories that Bolling School alums report align with the type of child-centric learning that now echoes through the halls of Greenbrier Community School.

Bolling School “was like a big family,” says Janice. “And that’s what the members of the Bolling-Clay Scholarship Committee felt when they [visited] the [GCS] classrooms. [They saw] teachers that were very passionate about what they were doing, very committed to what they were doing. The children were very happy, very engaged. And that’s the feeling that we all had as students here, when we were here as young people.”

When Greenbrier Community School redefined itself in 2019, one of its founding teachers, Jan Deaner, commented: “This school has always meant to be a community school, so how fitting that that’s finally its name.” How fitting, too, that—in the same year GCS chose a name that reflects its community calling—the school found a permanent home in the well-loved building of an historic community school.

At GCS, the alchemy of research-based, educational innovation and an intimate, homelike environment inspires a love of learning. Within this community context, children build essential skills like conscious communication and empathic leadership—human work that prepares each Greenbrier Community School student to change our shared world for the better.